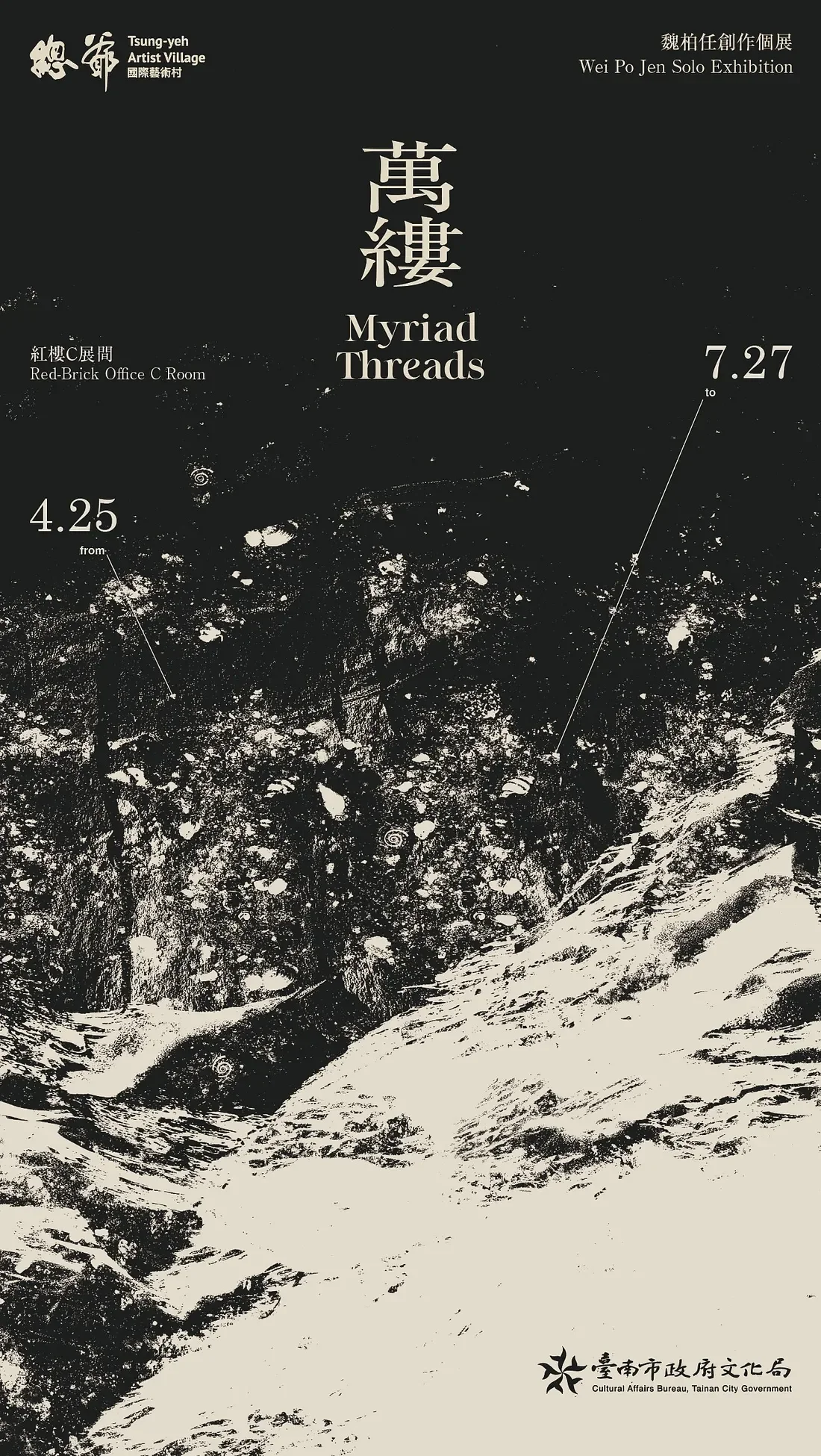

萬縷 Myriad Threads 魏柏任創作個展 Wei Po Jen Solo Exhibition

The entire exhibition room is a riverbank, and each of us, artworks and audience alike, becomes a vessel that carries stories through time.

萬縷|魏柏任創作個展 總爺國際藝術村 紅樓 C 展間 4.25–7.27

Myriad Threads | Wei Po Jen Solo Exhibition Tsung-yeh Artist Village 4.25–7.27

萬縷 Myriad Threads 魏柏任個展 資訊

.

萬縷,從搭車前往藝術村的路上就已經展開 — — 在車窗外的田園、在水道與古地圖的經緯、也在承載時間器物的裂縫中。

The myriad threads had already begun to unfold on the journey to the art village — in the fields outside the car window, in the waterways and the crisscrossing lines of ancient maps, and in the fractures of vessels that have carried the weight of time.

藝術家本人魏柏任 Artist Wei Po Jen, 照片來源:總爺藝術村

展間中,以「堤防」為意象的展架托著展品,除了用三合土 — — 牡蠣殼、糖漿、糯米漿(就是國小學到安平古堡的砌牆材料) — — 也有幾幅素描,其他藝術家看到驚呼:OMG, so multi-talented(噢買尬,真是多才多藝)

Inside the exhibition space, artworks are held upon stands inspired by river embankments. In addition to sculptures crafted from sanhé soil(三合土) — a mixture of oyster shells, syrup, and glutinous rice paste (the same materials we learned about in elementary school, used to build the walls of Fort Zeelandia) — there were also a few sketches on display. The visiting artists couldn’t help but exclaim, “OMG, so multi-talented!”

真的多才多藝,照片來源:總爺藝術村

而「堤防」本身是用灌水泥的模板切割而成,除了呈現堤防的輪廓,也形塑出如同地景沈積般的堆疊剖面。

The “embankment” itself was shaped using wooden forming boards — commonly used in constructing architectural structures, including river embankments. It presents not only the contours of a riverbank, but also layered cross-sections that resemble the sedimentation of a landscape.

「堤防」細部 Details of the “embankment”,照片來源:總爺藝術村

堤防的存在從來與人無法分割。人類傍水而居,卻又不得不設下堤防以對抗洪水,這種矛盾的親密感,被藝術家重新詮釋 — — 堤防是容器,把水承裝起來,捧在其中。

The existence of embankments has always been inseparable from human life.

We live by the water, yet we must build embankments to protect ourselves from floods — this paradoxical intimacy was reinterpreted by the artist: the embankment becomes a vessel, cradling water within its hollow.

但自然終究是無法馴服,館員分享,在八八風災中,展館曾經被腰深的淤泥覆蓋;來訪的民眾也分享了他們對天災的記憶。

And yet, nature remains untamable.

A staff member shared that during Typhoon Morakot, the gallery was once buried waist-deep in silt; visitors, too, shared their own memories of natural disasters.

來訪的蕭壠文化園區駐村藝術家杉原信幸(Nobuyuki Suguhara)分享道:「我們看不見堤防之下是什麼,這好像也反映了自然中那些被遮蔽的事物。」

Nobuyuki Suguhara, a resident artist from the Soulangh Cultural Park, offered his thoughts during our conversation:

“We can’t see what lies beneath the embankment; it seems to reflect the aspects of nature that remain hidden from us.”

柏任回應:「我也希望觀眾能夠看到背後的結構,讓一切被看見。」他補充,希望透過開放的結構(邊界沒有完全封閉),呈現出延展性與開闊的想像空間。

Po Jen responded,

“I also want viewers to see the structure behind it — I hope everything can be visible.”

He added that by keeping the structure open (without fully enclosing the boundaries), he hopes to convey a sense of expansiveness and unfolding imagination.

是真的一覽無遺,照片來源:總爺藝術村

堤防是容器、人體也是容器。

The embankment is a vessel, and so is the human body.

容器的詞彙中,口、肩、腹、腰、足、頸,甚至到唇、耳、眼等細部器官,都與人體有所對應;而附近的西拉雅文化中,壺與水、壺與信仰,也是無法分隔的概念。

In the language of vessels, terms like mouth, shoulder, belly, waist, foot, and neck — even lips, ears, and eyes — correspond to parts of the human body.

Nearby, in Siraya (a Pinpu Indigenous tribe) culture, the relationships between vessels and water, vessels and religious beliefs, are equally inseparable.

在展間裡,那些有口、有肩、有腹、有足的器物,如同人類自身 — — 盛裝時間,盛裝故事,也盛裝易碎的記憶。

In the exhibition space, those vessels with mouths, shoulders, bellies, and feet stand like reflections of ourselves — holding time, holding stories, and holding fragile memories.

展品中有容器、有手、腳、眼、耳,有些完整、有些碎裂。柏任說,就像考古現場,原本完整的事物,被再次發現時往往已經支離破碎。但透過考古學家的修復 — — 修復器物、修復它們的故事 — — 這些記憶又以某種新的「完整」姿態呈現。

Among the works are containers, hands, feet, eyes, and ears — some whole, some fragmented.

Po Jen said, just like at an archaeological site, what was once whole is often found broken. Through the hands of archaeologists — restoring the objects, restoring their stories — these memories are given a new form of “wholeness.”

容器 Vessels,照片來源:總爺藝術村

但什麼是真正的完整呢?再次召喚時光碎片大師班雅明(Walter Benjamin)。在靈光乍現的時代,攝影是記憶的證明 — — 而在你我之間交換的資訊(或者我平常都叫他「故事」啦),就是這些證明所存在的意義。

But what is true wholeness, really?

Once again, I find myself summoning Walter Benjamin, the master of time’s fragments.

In an era when photography served as the proof of memory, perhaps what we exchange between us — the memories and information (or, stories, as I usually like to call them) — is what truly gives meaning to that proof.

回到主題,在器物中、在堤防上、在時空之間 — — 這些有型、無形的千絲萬縷交織而成的是什麼?是所謂的靈光嗎?

Returning to the core: within the vessels, upon the embankments, across the tides of time and space — what are these myriad visible and invisible threads weaving together? Is this what we call the aura?

容器 Vessels,照片來源:總爺藝術村

我也開始想,這一整條曾文溪河道,是否就是這個空間中一切的匯集?一切都是追憶似水年華?

I also began to wonder: could the entire course of the Zengwen River itself be the convergence of everything gathered within this space?

In the end, isn’t it all just a remembrance of things past?

(怎麼每次都是大哉問結尾?

(Why does it always end with a big question?)

.

Learn more about the artist:

魏柏任 Wei Po Jen:Portfolio | Instagram @weiporen

And here’s a list of the AIRs in Tsung-yeh and Soulangh whose upcoming exhibitions I’m really looking forward to:

Tsung-yeh and Houlangh AIRs: Valentína Hučková, Matilde Stolfa, Peter Baron, Wei Po Jen, Nobuyuki Suguhara, and Ayaka Nakamura (Left to right),照片來源:總爺藝術村

【總爺國際藝術村 Tsung-yeh Artist Village】

Matilde Stolfa (Netherlands): Portfolio | Instagram @matildestolfa

許懿婷 Hsu Yi Ting (Taiwan): Portfolio | Instagram @hsuyiting_g

【蕭壠文化園區 Soulangh Cultural Park】

Peter Baron (Slovakia): Portfolio | Instagram @regularconcrete

Valentína Hučková (Slovakia): Portfolio | Instagram @valentinahucko

杉原信幸 Nobuyuki Suguhara & 中村綾花 Ayaka Nakamura (Japan): Instagram @nobuyukisugihara.ayakanakamura

杉原信幸Nobuyuki Suguhara: Portfolio | Instagram @nobuyukisugihara

中村綾花 Ayaka Nakamura: Portfolio | Instagram @ayaka.hatter

.

最後用號稱很像英文課本的照片作結(朋友:是教科書等級的攝影!),謝謝總爺藝術村的邀請以及授權使用美麗的照片,現場感受到藝術品跟空間的互動又是另外一種美,真的是可以儘速去看看。

Textbook-level photography with Peter Baron, Valentína Hučková, and Matilde Stolfa,照片來源:總爺藝術村